The fact that the new templates appear 18 years after FIDIC launched its first ‘Rainbow' suite demonstrates FIDIC's lead position in international engineering procurement.

Add to that FIDIC's history - it is over 100 years old and its Red Book dates back to 1957 - and the fact that its contracts have been tried and tested around the world, and FIDIC's status is clear.

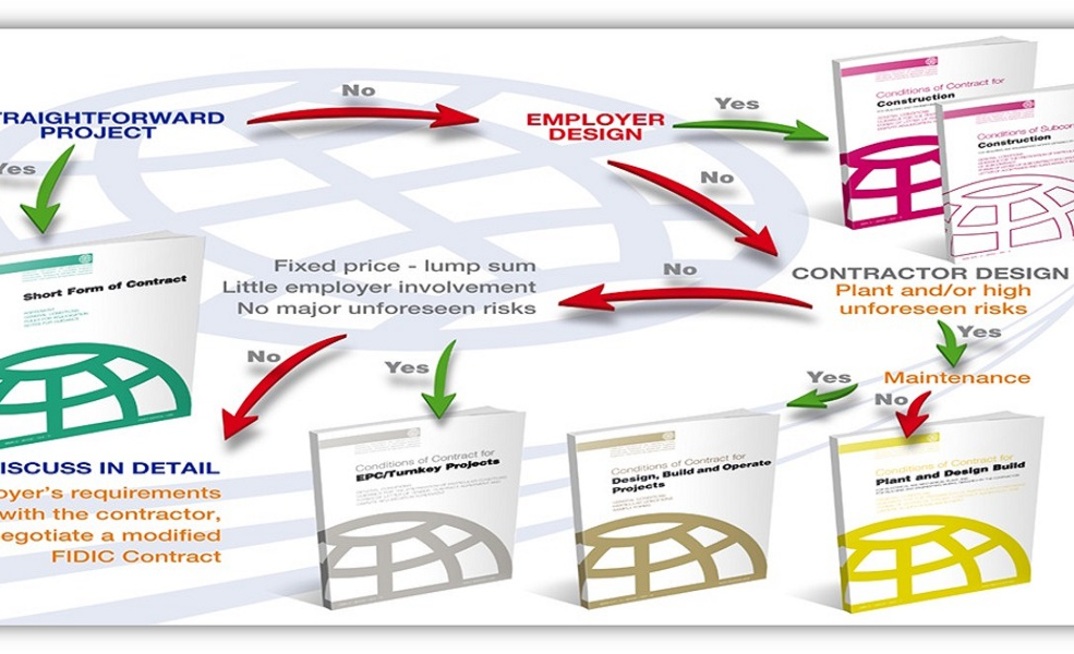

Mining projects often use FIDIC-based engineering and construction contracts and FIDIC's Silver, Yellow and Red Books are ones we see most.

Mining contracts have to be drafted to match the specifics of each given project and bespoke amendments to the standard forms will always be required. When considering what changes need to be made, it is important to bear in mind the differences between a mining contract and a construction contract. An obvious example is how the contractor gets paid. Another example is the plant that is typically used for the operations - the large earthmoving equipment that is required and the spare parts needed to service it; these may well be provided by the employer.

Before looking at FIDIC's new forms (FIDIC 2017), it is of paramount importance to fully understand the implications of UK Supreme Court decisions such as MT Højgaard A/S v E.ON Climate & Renewables UK Robin Rigg East Limited and another (2017), when putting together contracts under English law.

In Højgaard, the Supreme Court found the contractor liable to comply with a fitness for purpose type obligation that was "tucked away" in a technical schedule to the contract - despite obligations in the agreement itself to exercise reasonable skill and care. We all know that the finer detail of each and every project needs to be fleshed out in the employer's requirements documentation/output specifications; this case acts as a warning that extra care must be taken with multi-authored documents.

Højgaard is generally viewed as another example of a return, in emphasis, to the literal meaning of contract provisions following the Supreme Court's decision in Arnold v Britton (2015).

Definitions and interpretation

It is therefore to be welcomed that FIDIC 2017 has revamped its introductory provisions to include many more definitions (it now lists them in alphabetical order and introduces more headings) and a much broader interpretation clause that extends to defining words such as "may", "shall" and "consent" to help improve interpretation by non-native English speaking users.

The key features of the new forms include:

• More detailed contractual provisions (hence longer agreements) and guidance;

• A broadening of the concept of communication through "Notices";

• An expanded role for the engineer;

• Variations and claims to be dealt with as they arise;

• More reciprocity of obligations between the parties;

• A distinction between a "Claim" and a "Dispute", with the old clause 20 being split into two provisions; and

• The introduction of ‘dispute avoidance'.

Reciprocity and contractual and project management mechanisms

In mining projects, promoting collaboration between the parties is to be encouraged.

There are benefits in allowing the employer to participate in a number of areas - including the location of operations, plant maintenance, stock control and procurement.

The clauses in FIDIC 2017 have been expanded to promote greater reciprocity between the parties.

To this end, FIDIC 2017 contains both more detailed procedures as well as new ‘tools'. An example is the NEC-style ‘early warning system' which is aimed at encouraging issues to be aired and tackled early on. In addition, a wider role for the engineer will require more active project management and there is also a new role altogether - the site-based 'engineer's representative', who is to be on site for the entire duration of the works.

Dispute avoidance, management and resolution

Given the very nature of mining projects, the scope for differences of opinion and conflicts to arise is wide and the provisions relating to the management of disputes become more important.

FIDIC 2017 has seen an overhaul of the fundamental concepts that underpin contract-based claims being brought by either party (against the other), the actual dispute resolution procedures (between the parties), the contractual conditions that govern the separate disputes agreement and the procedural rules that apply (these are set out in an Appendix to the General Conditions and the Annex to that Appendix).

It would be fair to say that FIDIC's approach to dispute management and resolution constitutes one of the hallmarks of FIDIC 2017.

There are a number of standout provisions in particular around employer's claims, which are no longer dealt with in Clause 2 - these are now provided for in Clause 20 and there is consistency of treatment between employer and contractor claims. This is significant because employers will now have to follow a more rigorous claims and determination procedure (which includes a number of time bars and deemed) than under the previous FIDIC forms meaning that the state of limbo that the employer used to be able to rely upon to avoid a contractor bringing on disputes has now been significantly curtailed.

FIDIC 2017 now includes a new Clause 21 - the parties' ‘day-to-day' claims have been separated from ‘disputes' between them (now defined).

The new provisions also emphasise the engineer's/employer's representative's neutrality, so when dealing with claims, there is now a more structured step-by-step procedure, with time limits. The philosophy here is to deal with issues as they arise and not save them up to the end and the engineer/employer's representative is very much on the front line.

The Dispute Adjudication Board (DAB) has been converted into a Dispute Avoidance/Adjudication Board (DAAB) which is now constituted at the outset, as a permanent board, for the duration of the project and its role has been extended greatly to include dispute avoidance - a new theme across FIDIC 2017.

It's also worth noting that while the above features seem positive ones, both parties need to be fully aware of the greater procedural requirements that are being placed on them (and on the engineer's/employer's representative too), which have the potential to expose both parties to greater liability - for example, a simple failure to comply with the contract's strict notice requirements (and serve them on time).

The parties need to bear in mind the grave consequences that may follow from the multitude of new 'deeming' provisions (which are designed to keep the project moving and on track).

FIDIC's Golden Principles

FIDIC 2017 includes (within its guidance) certain ‘Golden Principles' - principles which it considers to be inviolable and in accordance with which FIDIC-based contracts should be negotiated.

These are:

• The duties, rights, obligations, roles and responsibilities should generally be as implied in the general conditions;

• The particular conditions must be drafted clearly and unambiguously;

• The particular conditions should not change the balance of risk allocation provided for in the general conditions (they must be drafted in compliance with the Abrahamson Principles, namely that risk should be allocated to the party in the position to control them);

• The parties should have a reasonable time in which to perform their obligations and exercise their rights; and

• All formal disputes must be referred to a DAAB for a provisionally binding decision as a condition precedent to arbitration.

These are helpful benchmarks for contract negotiations.

New forms and another new contract on the horizon

As with any new contract that appears in the market, the devil is in the detail. FIDIC users and those interested in the new forms need to ensure they are up to speed on the new features and the Golden Principles.

Ahead of us, on the horizon, we look forward to welcoming an addition to FIDIC's suite - a new tunnelling contract, FIDIC's eagerly awaited ‘Emerald' Book, which is designed to manage the geological, geotechnical and structural risks specific to sub-surface projects which will provide further, much needed clarity for such contract negotiation.

*Partner Mark Berry and associate Matt Hacking work in global law firm Norton Rose Fulbright's mining practice.