In June 2019, China's state planning agency hosted an expert meeting to discuss measures to strengthen export controls on rare earth elements; a group of 17 strategically important metals with an array of high-tech applications from fighter jets and missiles to mobile phones and electric vehicles.

Hugo Brennan, Verisk Maplecroft

The event was just one among a series of recent signals from Beijing around its ability and readiness to restrict rare earth exports to the US, as China seeks leverage in an increasingly combative trade war that has evolved into a wider strategic confrontation.

This drum beat of veiled threats from Beijing is shining a spotlight on America's heavy import dependence for the array of minerals and metals needed to power the green-energy transition and high-tech digital economies of the future.

The combination of China's dominant position across a host of mineral value chains and the potential for Beijing to cut off access to these critical materials has been rightly identified by the Trump administration as a potential strategic vulnerability in need of a comprehensive policy response.

While rare earths are hitting the headlines now, they are the canary in the coal mine. More mainstream materials that the Trump administration has also designated as "critical" to economic prosperity and national security - such as aluminium, tin, cobalt and lithium - are likely to receive similar political attention over the coming decade.

US reliance on critical minerals, including from China

Key points:

- Beijing's threat to restrict rare earth exports to the US has underscored America's dependence on imports of critical minerals

- China enjoys a dominant position across a host of mineral value chains and may seek to use this advantage as geopolitical leverage

- Boosting domestic production and sourcing more critical minerals from friendly states would lessen America's reliance on China.

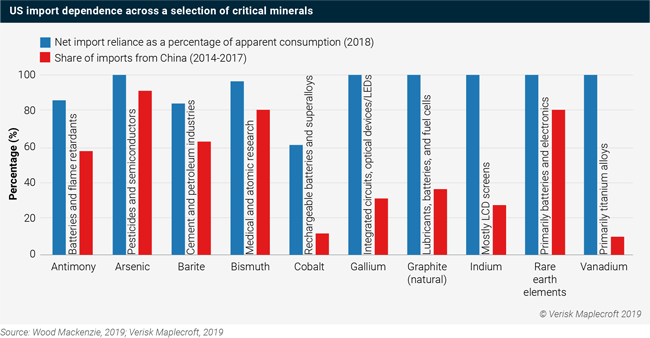

The US currently imports at least 50% of its supply of 29 out of the 35 minerals and metals that the Trump administration has designated as "critical". More starkly, the world's largest economy lacks any domestic production for 18 of the 35 critical materials (see Figure 2). Furthermore, in many cases, the US is reliant on China for the bulk of these imports; a state that the Trump administration identified as a strategic competitor in its inaugural national security review in December 2017.

Beijing's threats to halt rare earth exports to the US have only reinforced growing strategic concerns in Washington about the nation's vulnerability to mineral supply-chain disruption, particularly in the event of heightened geopolitical tensions with China. While the magnitude of damage that export restrictions on critical minerals would create is hard to estimate, it would likely result in significant dislocation to the US economy and defence industrial base.

Washington's concerns are not unfounded either, as Beijing has form on this front. Most notably, the Chinese government restricted rare earth exports to Japan in 2010 amid a geopolitical spat over the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands. Cutting off critical mineral exports to the US would come at some financial and reputational cost and would not be undertaken by Beijing lightly. However, the trade war already provides proof of China's ability to absorb economic pain in pursuit of its strategic goals.

China dominates many critical mineral value chains

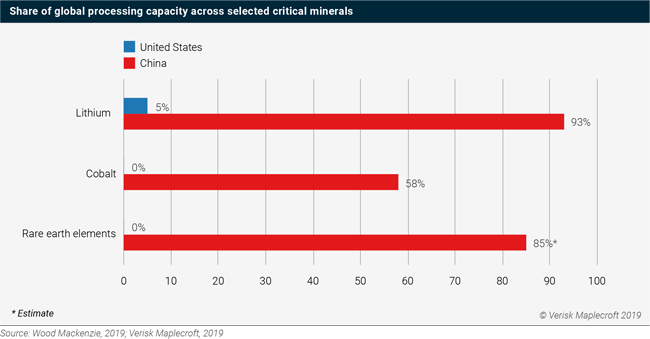

Beijing's readiness to use rare earth exports as geopolitical leverage is premised on its dominant position within the global value chain. China accounts for approximately 70% of mined rare earths output and is home to roughly 85% of the world's processing capacity. The US currently has just one operational rare earth mine - the Mountain Pass project in California - but must export the asset's rare earth concentrates for processing in China, swallowing a 35% tariff levied by Beijing in the process. Chinese rare earths miner Leshan Shenghe Rare Earth Co also holds a non-voting, minority interest in the project.

China's dominance across strategically important mineral value chains is not restricted to rare earths; a situation that is rooted in both the country's rich mineral endowment and the government's ongoing and proactive efforts to build a world class metals industry. China is the leading producer of 19 of the 35 minerals and metals that the Trump administration has labelled as critical, including aluminium, tin, manganese, titanium and natural graphite.

Beijing has also been actively encouraging its companies to go out and secure the upstream supply of mineral resources that China is itself import dependent on. For example, China's cobalt reserves are comparatively small, but Chinese companies now account for about half of the mined cobalt in the DRC - the world's largest producer by a country mile.

Moreover, China dominates downstream processing of the commodity by virtue of being home to 58% of cobalt refinery capacity globally. It is a similar story for lithium, where approximately 60% of lithium production is now under the control or influence of Chinese companies and China itself is home to 93% of lithium processing capacity globally (see Figure 3).

The Tenke Fungurume mine in the DRC is a major global cobalt supplier and is 80%-owned by China Molybdenum Co (Credit: Tenke Fungurume Mining)

Reducing dependence a long-term endeavour

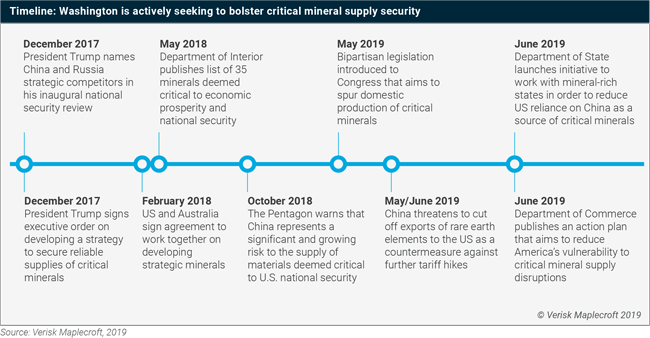

The Trump administration is not standing idly by but is taking concerted steps to reduce America's dependence on critical mineral imports from China. An action plan released by the Department of Commerce in June called for a multi-pronged approach to increase domestic exploration, production, processing and recycling.

Example recommendations include improving access to relevant geospatial data, streamlining the protracted federal permitting process, opening up more federal land to mining, and providing incentives to facilitate the brining online of new mines and processing facilities. All of these proposals would be well received by potential investors, but some will be opposed by the country's environmental lobby.

Another avenue that the Trump administration is targeting is the development of "mineral alliances" with resource-rich allies such as Canada, Mexico and Australia. By working with friendly states to develop their own critical mineral deposits, the US aims to diversify away from a reliance on imports from less friendly states.

Canberra has been particularly active in terms of marketing Australia as a reliable source of raw and refined critical minerals via the release of its own critical mineral strategy and its active promotion of projects that would dilute China's control over mineral value chains. Non-Chinese producers of critical minerals are likely to find political favour in Washington and enjoy an advantage over their Chinese peers when selling into the US market. Similar ‘secure supply' premiums may also emerge in other China-wary markets such as the EU and Japan.

Nevertheless, reducing America's reliance on critical minerals mined and/or processed in China is a long-term ambition rather than an immediately obtainable policy goal. China will continue to dominate critical mineral value chains for the foreseeable future and will likely be tempted to use its unrivalled position as leverage during future geopolitical flare-ups with the US.

The geopolitics of critical minerals therefore looks set to evolve beyond its current focus on rare earths and become a defining issue for much of the metals and mining sector over the coming decade.

*Hugo Brennan is head of mining for global above-ground risk consultancy, Verisk Maplecroft

ABOUT THIS COMPANY

Verisk Maplecroft

Verisk Maplecroft is a leading global risk analytics, research and strategic forecasting company offering an unparalleled portfolio of risk solutions.

HEAD OFFICE:

- 1 Henry Street, Bath, BA1 1JS, United Kingdom

- Phone: +44 (0) 1225 420000

- Website: www.maplecroft.com/

- Email: info@maplecroft.com