When the United States and Canada announced their joint action plan on critical minerals collaboration in January 2020, little did anyone know that dozens of similar agreements would follow in the next four years.

Mining Journal and sister publications have compiled a list of critical minerals agreements since 2020. The tally came to 38 in March 2024 when Australia and Canada signed a joint statement on critical minerals cooperation on the sidelines of the PDAC conference in Toronto.

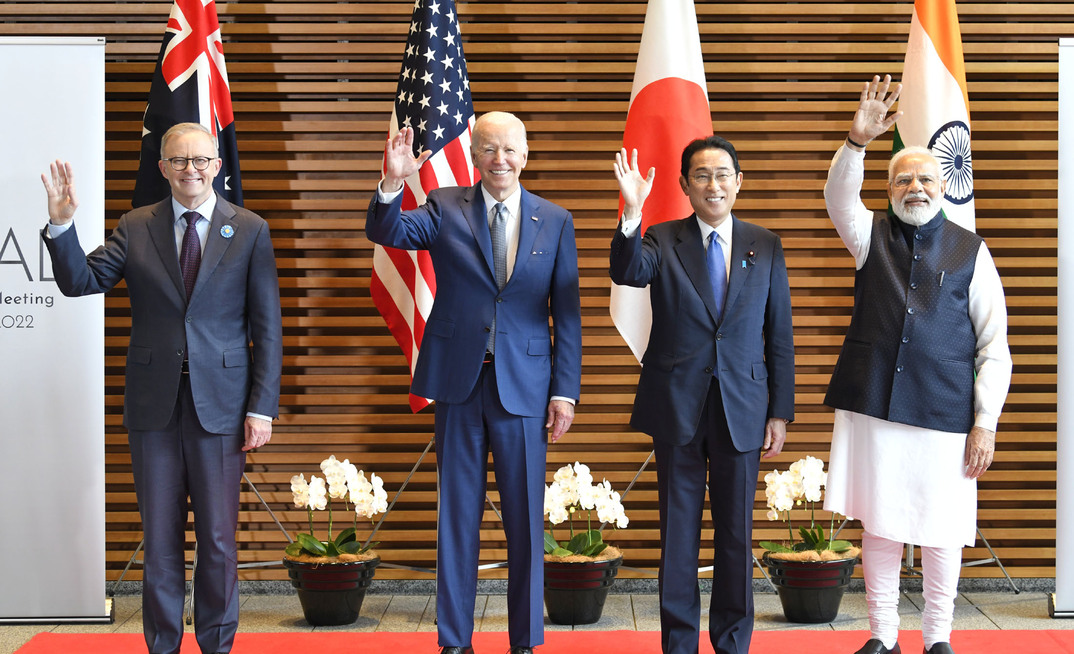

Our list contains six multilateral agreements, including the US-led Minerals Security Partnership (MSP), which expanded its membership to 15 with the addition of Estonia in March; the Sustainable Critical Minerals Alliance, a Canadian-led initiative involving seven MSP members; and the Quad Statement of Principles on Clean Energy Supply Chains in the Indo-Pacific, between the US, Australia, India and Japan.

There are also 32 bilateral agreements, the most recent being the EU-Rwanda memorandum of understanding to enhance sustainable and resilient value chains for critical raw materials in March 2024.

Our list is notable for the absence of one country: China.

The Minerals Security Partnership and similar initiatives reflect the concern of many countries over China's dominance of critical minerals, according to Lachlan Nieboer, founder of Bedford Analysis, an advisory service specialising in the geopolitics of critical minerals supply chains.

"The values and the purpose of the MSP are for the task at hand, which is really this China piece, There's a national security element, obviously, it's in the name. It's about the relationship between allies on security issues," Nieboer said.

"We have a question that is China. And we don't know how to solve it. And in whichever field – if you're picking a strictly defence-related subject and it's nothing even to do with minerals – we're still asking the same question: how do we deal with this?" he continued.

"This web of security partnerships – the Quad [between Australia, India, Japan and the US], AUKUS [Australia, UK, US], Five Eyes [Australia, Canada, New Zealand, UK, US] – are all sort of integrated. They're distinct and different, but they're part of the same story in a way, which is that from 50,000 feet the world is slowly fragmenting."

John Coyne, head of the Northern Australia Strategic Policy Centre at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), said there were economic, environmental and geopolitical angles to the boom in critical minerals agreements.

"On the economic and environmental [front], in terms of critical minerals, the demand curve, especially for the energy transition, is significant. Current projections are going to fall short of that demand over the next decade or two," he said.

"On the other side of that equation is a geopolitical one, which relates to supply chains and market disruptions – which we've seen recently with nickel and lithium. Some will understand that as a market correction, and there can be no doubt that there was a market correction at some level. But the other side of it – and certainly we've seen this in the rare earth market –is that at certain critical times, Chinese companies have flooded the market with supplies of rare earths to distort the market and prevent other competitors from entering."

Coyne said governments – including Australia's – had begun to understand that they could play a role in promoting mining and processing of critical minerals while still upholding the principles of a market economy.

"For [the past] three decades Australia has most definitely bought into economic liberalism. In doing so, it's put a great deal of emphasis on market forces. Things like just-in-time supply chain, decentralisation of production, offshoring, industry hubs, processing hubs, etc., all these sorts of things have created a great deal of wealth for many countries, including Australia," he explained.

"But in the meantime, the Australian government's experience of pulling economic levers and intervening in its economy has become a muscle that's atrophied."

Coyne sees Australia's involvement in critical minerals agreements as a "gateway" to addressing supply chain bottlenecks, but that it is heavily reliant on the private sector "actualising" these agreements.

"[These agreements] do have some impact, and they certainly assist in creating an environment, often de-risking some projects for investment and exploration work, so that they're not without value. But they do come with a commitment, they do come with a cost in terms of engagement: when you have so many agreements, engaging in multiple directions, is really, really difficult," Coyne said.

"I think that the real issue here is that market intervention is needed. And one of the greatest challenges for most critical minerals, including rare earths [is that] you're not talking about bulk exports like coal and iron ore. And so as a result of that there's a tendency, a very difficult trend in actually being able to raise the necessary capital to create mines and supply chains and value chains as well, for that matter."

As part of his role at ASPI, Coyne was one of the organisers of the 2023 Darwin Dialogue, which brought together Australian, Japanese and US government and industry representatives to discuss critical minerals supply chains. The event will take place for the second time this April, with South Korea joining as a full partner and observers from India, Indonesia, the Netherlands, Taiwan and the United Kingdom also planning to attend.

The event fills a space between formal government diplomacy and informal private sector meetings, according to Coyne. It brings together an "eclectic" group of people from government ministers to economists to geologists. It takes place under Chatham House rules, to encourage individuals to speak freely about the subject matter.

Coyne believes the forum proves the value of ‘minilateralism' – defined by Australia's Lowy Institute as a collaboration between a group of countries to address a specific challenge that larger multilateral structures are ill-suited to handle – in helping likeminded countries create alternative supply chains for critical minerals.

He said the first Darwin Dialogue produced tangible results, including a closer connection between the Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corporation (JOGMEC) and the government of Australia's Northern Territory, where the event is held. It also spurred a number of countries, as well as the EU, to enquire about attending future events.

Ultimately, Coyne said, "What we're trying to do is not replace all those other things that are done. What we're trying to do is bring all those voices together, so we can get not a common understanding, but a better a better sort of combined understanding of what the challenges are in terms of creating resilient, alternative, competitive and ESG-compliant supply chains."

This is the third in a special series on critical minerals strategy. The previous articles were Revealed: the two little-known minerals deemed 'critical' by every major economy; and Exclusive: Tracking the flow of US critical minerals funding.